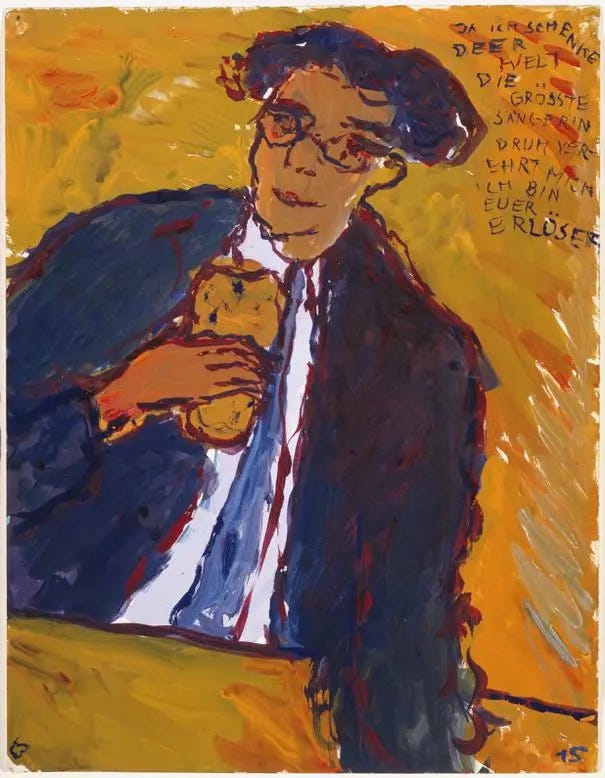

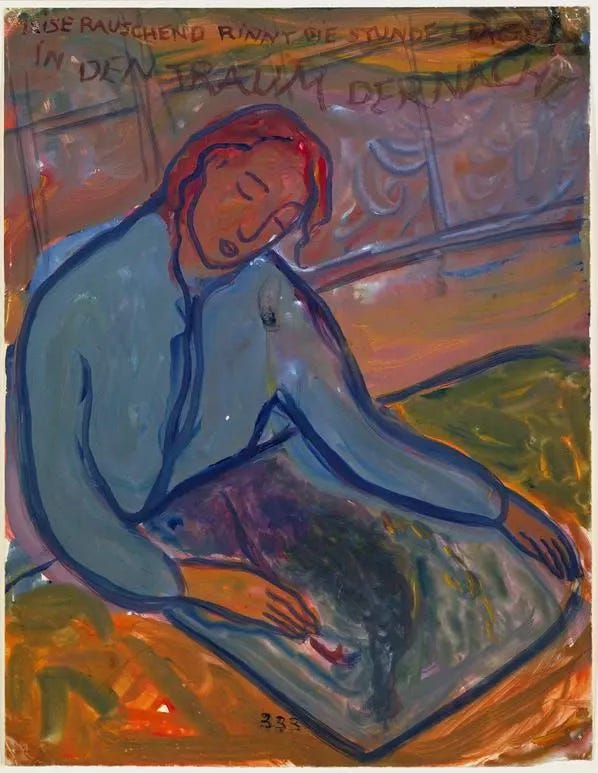

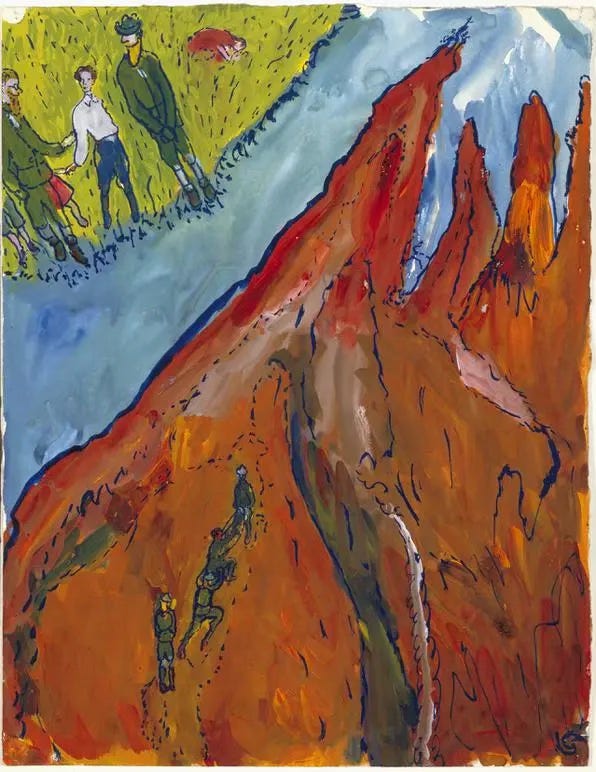

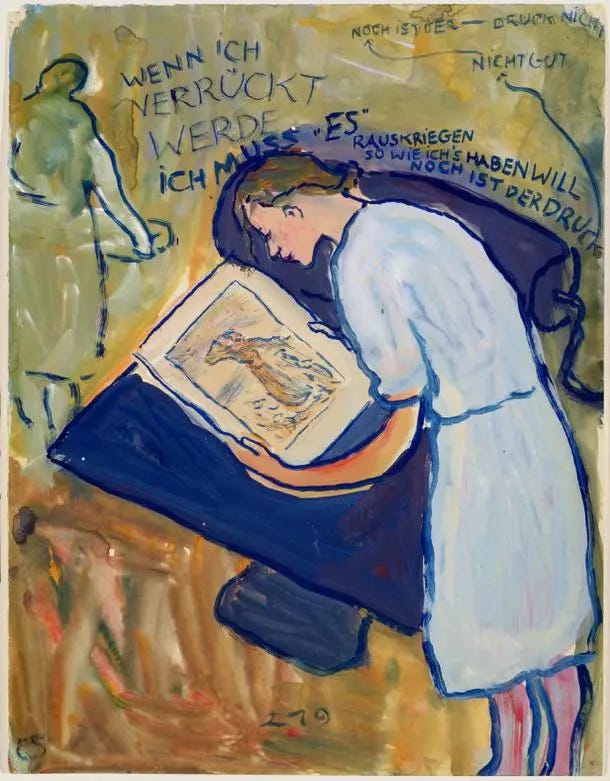

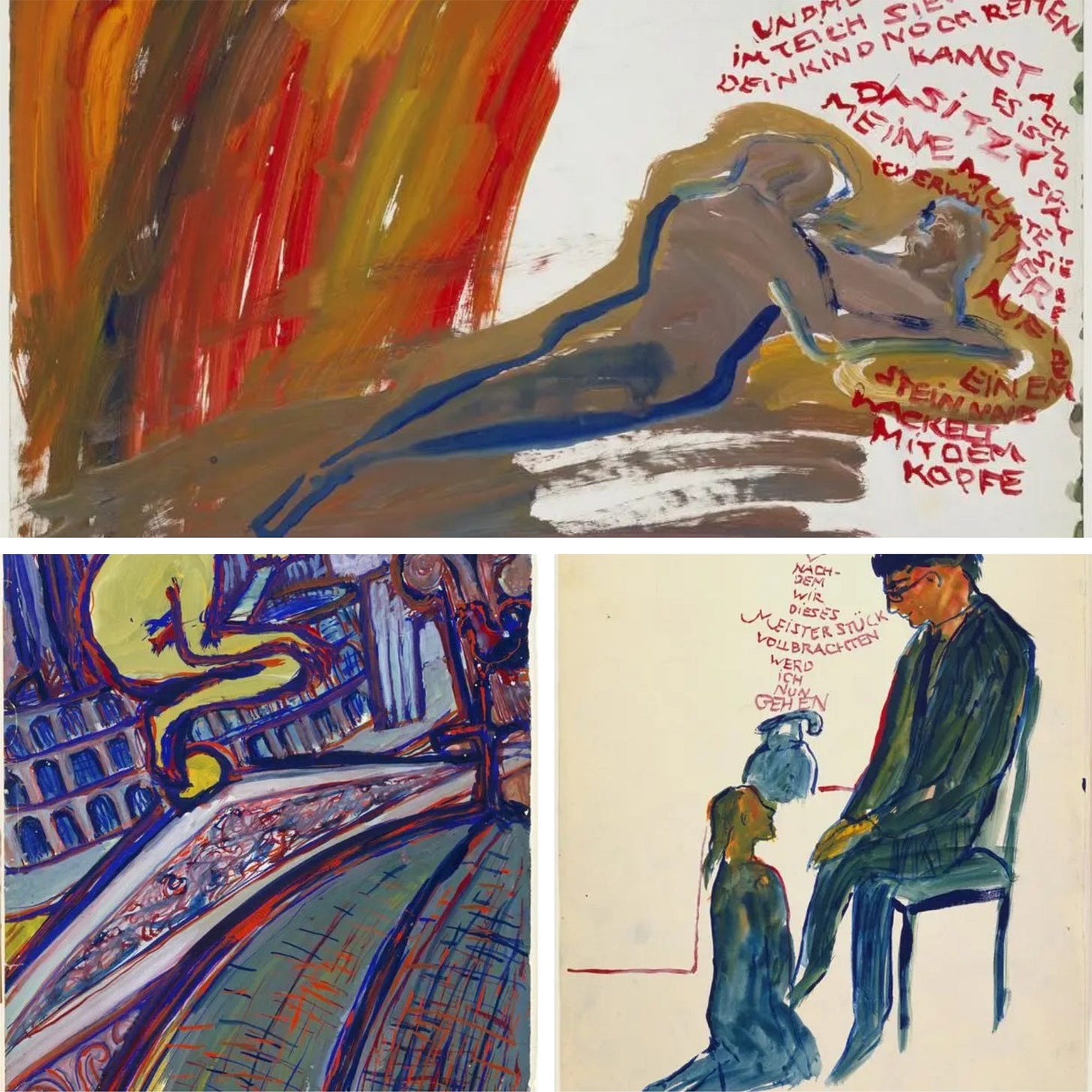

Charlotte Salomon found a haven not far from Villefranche, at a hotel in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. There, she created her great work, an integrated series of paintings-and-words, which she called Leben? oder Theater? (Life? or Theatre?) and subtitled ‘ein Singspiel’, a German sung and spoken opera. In it, she retraces her entire life from her birth to the moment she is painting, giving pseudonyms to her family and friends: Kann for her parents, Amadeus Daberlohn for Alfred Wolfsohn. In the early 1940s, she was still in love with Alfred, painting him obsessively, but her accompanying text is often tongue-in-cheek.

In 1943, not long before her arrest, she handed the whole of Leben? oder Theater? over to her doctor and friend, Dr Moridis, for safekeeping, telling him: ‘Guard them well: this is my whole life’.

In June 1943, she married a fellow exile, Alexander Nagler, whom she had met through Ottilie. Their benefactress had left France in 1941 with a group of child refugees. Rejected from all lodgings, either because they were Jewish or because they were German, the young couple lived in Ottilie’s empty home in Villefranche-sur-Mer, l’Ermitage, their hermitage and refuge.

She was five months’ pregnant when the Nazis caught up with her. After Italy left the war in September 1943, Germany invaded the the French Riviera, previously occupied by Italy. Charlotte and Alexander planned to flee to Italy, but the sea route was blockaded and Alexander, injured years earlier and still limping, couldn’t hike across the mountains to the Italian border.

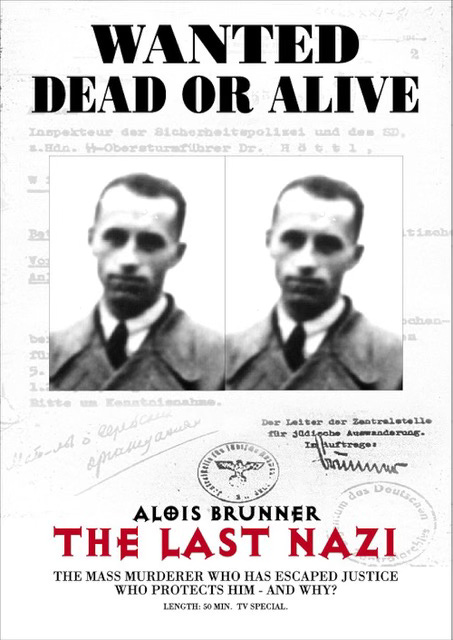

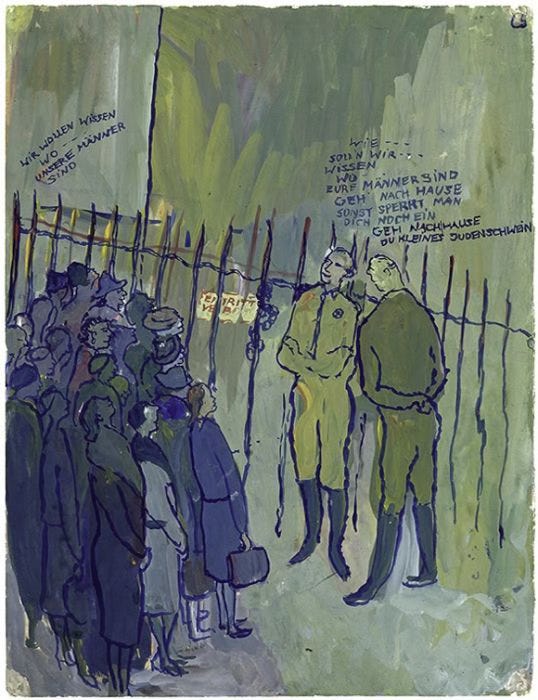

To round up the Jews of the Riviera, Himmler had sent to Nice a notorious Austrian Nazi and psychopath, Alois Brunner, who had already worked his dark arts in Austria and Salonica, Greece. Later, he was to find refuge in Hafez Al-Assad’s Syria, where he mentored Assad’s goons in torture techniques. His date of death is unknown: he might have died naturally in 2010, in an Assad dungeon in 2001, after Bashar Al-Assad had succeeded his father. At the time David Foenkinos wrote Charlotte, it was believed he had died in the 1990s. Brunner was never captured nor tried in Europe, despite the best efforts of Simon Wiesenthal and Beate and Serge Karsfeld, multiple request to extradite him by France and Germany and an Interpol arrest warrant. He never expressed regret, quite the opposite: he remained a hate-filled antisemite.

Following an anonymous tip-off by phone - never traced - informing the Nice Gestapo of ‘a German Jewish artist, a woman, living in the house called l’Ermitage at Villefranche-sur-Mer’, the police turned up to arrest Charlotte. Alexander, who was not on their lists, insisted on coming too to care for his pregnant wife.

At the hotel Excelsior, the headquarters of the SIPO-SD in Nice, Brunner was busy yelling at the rounded up Jews and torturing detainees. But he also said to them: ‘we’ve founded a Jewish homeland in Poland, and we’re taking you there.’ He added that he didn’t want any fuss, so if anyone in a train carriage tried to escape, everyone else would be shot.

Charlotte, Alexander and their fellow deportees were transferred to the transit camp of Drancy, in northeast Paris. After a few days, guards crammed them into cattle wagons for Poland, with no food and no water for the journey. Arriving at their destination after three hellish days, they read the now notorious slogan: Arbeit macht frei. I can’t help wondering - did any of them ever fall for the ‘Jewish homeland’ lie that Brunner spun them? I doubt it - but did they know that most of them were going to their deaths rather than to a work camp? In the book, a young man tries to escape from the train on the way, and is prevented by the others. Despite dreading their unknown destination, they didn’t want to be shot: hope can be stronger than fear.

In Auschwitz, the couple was separated. Alexander was put to hard labour on 600 calories a day and was worked to death after three months. The Nazis gassed Charlotte and her unborn child on arrival. She was 26 years’ old.

And what happened to Leben? oder Theater?, the precious work she had hidden with Dr Moridis?

Charlotte’s father and stepmother had survived the German occupation by hiding in Amsterdam. After the war, they went looking for their daughter in the South of France, and discovered her fate. Ottilie Moore, back from the United States and living in l’Ermitage again, had met up with Dr Moridis, who handed over Charlotte’s paintings to her. She gave them to Albert and Paula.

In the novel, they are shaken by her artistry and vision - Charlotte’s whole life in gouache, watercolours and words. Shaken and sometimes shocked by the revelations they saw and read in the paintings.

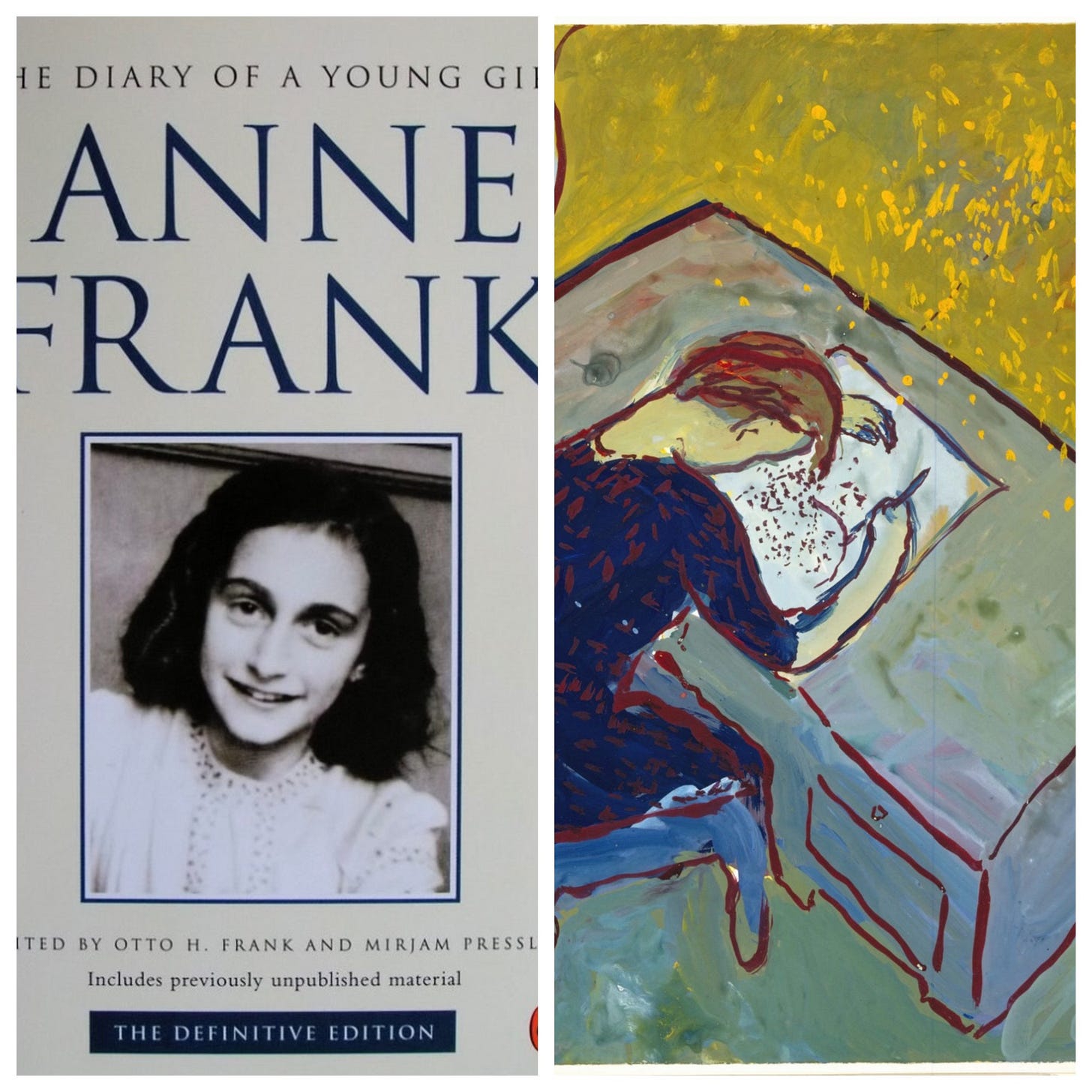

They travelled back to Amsterdam with Leben? oder Theater? carefully boxed and wrapped. This detail isn’t in the book, but I found it when I went looking online: at first, they only showed the paintings to Otto Frank, Anne Frank’s father, their friend and fellow German Jewish refugee. How must their conversations have gone, when they discussed their gifted daughters, murdered in their youth by an antisemitic regime and its sadistic executives?

In 1971, after several shows, they gave Charlotte Salomon’s works to the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam. In the book, we’re told it’s kept in a basement storage most of the time, with the implication that it should be on permanent show. There have also been several exhibitions around Europe, including in her native Germany, where she is now recognised as an important German artist of the 20th Century. On the website of the Joods Cultureel Kwartier, they explain that the whole collection is too fragile to be exposed permanently, but that they rotate 6 gouaches, and show the collection of Leben? oder Theater? online.

Charlotte Salomon was a complex and experimental painter, at times playful, at others unsettling or tragic, reflecting her life. David Foenkinos conveys those different sides of Charlotte in his novel. Yet her work is more than painting: it is at the same time art, autobiography and historical document, a combination that touches the mind, the heart and the soul. As Charlotte herself did.

Charlotte, by David Foenkinos. French original published in 2014; translated into English by Sam Taylor for Canongate Books.